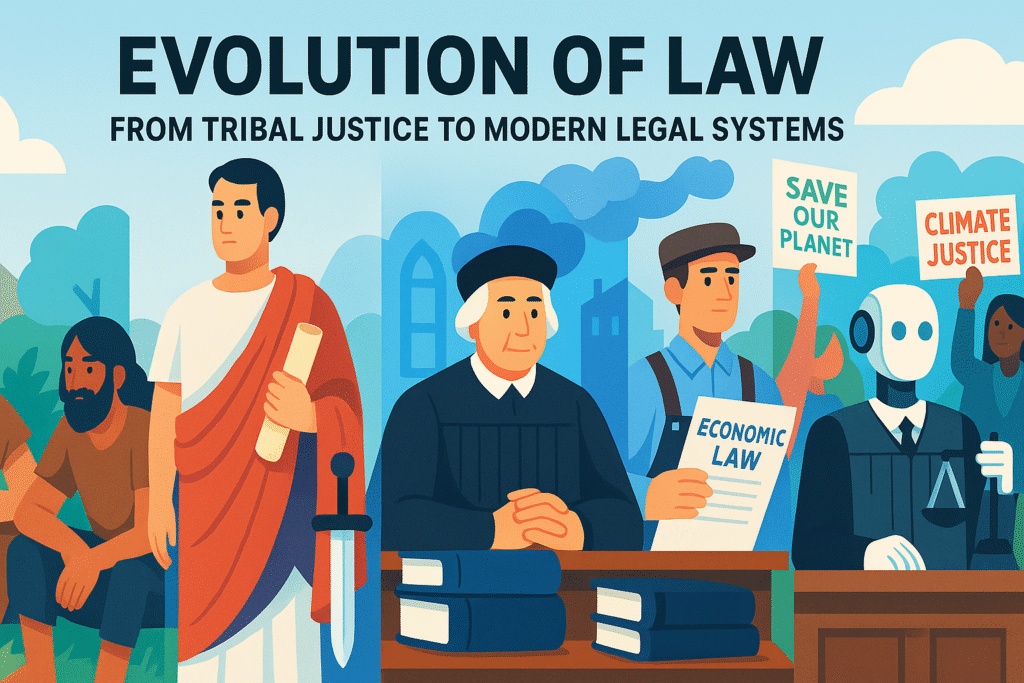

Evolution of Law

1 Constitution. 25 Parts. 448 Articles. 12 Schedules. 6,779 Acts. Thousands of rules and regulations . Sounds massive? It is. But all of it began with something surprisingly simple — our natural inclination toward justice.

Law didn’t drop from the sky. It evolved — from tribal instincts to constitutional rights, from revenge to regulation. This is not just a timeline of legal history. It’s a story of how humans built rules to survive, thrive, and sometimes… control.

1. Tribes – The Birth of Justice

Natural morality. Fairness. Reciprocity. Justice without written law.

At the dawn of humankind, there were no written codes. No statutes. No courts. Yet, early human communities somehow upheld a sense of fairness — relying on shared instincts of right and wrong.

A study by the University of Central Florida found something fascinating: ancient legal codes from far-apart civilizations often mirrored each other. Even today, participants of a study from modern India and the U.S. intuitively agreed with 3,800-year-old Sumerian laws. That’s no coincidence. It points to a natural, cognitive bias toward justice — hardwired into us.

Back then, laws were nothing more than oral traditions. Norms were passed down, enforced through collective approval, and maintained through custom. The responsibility for justice? Often personal. In these early pre-state societies, it was up to the kin of victims to enforce the rules.

Ancient Greek and Roman systems required victims or their families to apprehend offenders and present them before magistrates. This worked — until societies grew more complex. In diverse, expanding urban centers, justice could no longer be personal. It needed structure. It needed authority.

⚖️ Fun fact: The Germanic concept of wergild (“man-price”) allowed offenders to pay monetary compensation to avoid blood feuds — a clever workaround echoed in Anglo-Saxon and Norse laws. Justice, but make it negotiable.

2. Kingdoms – Codifying Control

From customs to codes; priests and rulers enforce shared norms.

As populations swelled and cities replaced tribes, informal customs struggled to contain growing complexities. Disputes over land, labor, and livestock demanded something more consistent—enter the age of written codes. One of the earliest, the Code of Urukagina (c. 2380–2360 BCE), emerged in Sumer not just to resolve conflicts but to centralize authority. These early laws formalized compensation for harm—like fines for theft or damage—reflecting the rhythms of agrarian life.

Religion, too, played judge. In Mesopotamia, temple administrators acted as legal arbiters, deciding matters from disputes to inheritance, blurring the line between divine will and civic order. Ancient Egypt took it further: ma’at—the idea of cosmic balance—was law itself. Pharaohs weren’t just kings; they were enforcers of the universe’s moral code, tasked with preserving harmony through decree.

Written law became a tool of power. Rulers weren’t just organizing justice—they were codifying control.

⚖️ Fun fact: Babylonian law didn’t take kindly to lies in court. Commit perjury? You could be fined up to 15 shekels of silver—roughly half a year’s wages for a laborer.

3. Empires – Law Goes Imperial

The rise of centralized institutions, formal enforcement, and religion-law fusion.

As empires expanded, the need for structured justice became undeniable. In ancient Rome, Augustus established the Praetorian Guard (27 BCE) to maintain order and enforce laws, while lictors carried fasces—bundled rods symbolizing punitive power. In medieval England, shire-reeves (sheriffs) were tasked with tax collection, law enforcement, and even having the power to call on local citizens to help enforce the law.

Across the Islamic world, the Abbasid Caliphate employed muhtasibs—market inspectors responsible for enforcing commercial laws and public morality under Sharia law. Meanwhile, many non-European societies, like the Ashanti Empire (modern-day Ghana) and pre-colonial India, balanced local customs and royal decrees, creating a unique legal framework that prioritized relationship restoration over rigid legal codes.

However, the legal systems of these empires and cultures were soon to face a massive disruption. The rise of colonialism would bring a uniform, centralized legal system, fundamentally altering the way law was administered across the globe.

⚖️Fun Fact: The fasces symbol, carried by Roman magistrates, is still used today in the United States as a symbol of unity and authority, most notably on the Lincoln Memorial.

4.Nations – Laws of the People

Nationalism replaces monarchs; colonialism imposes foreign laws.

By now, you’ve seen how law evolved from governing tribes to governing empires. But a new force was on the horizon: nationalism—and with it, the rise of nation-states that redefined legal systems. Nationalism turned fragmented feudal laws into unified, country-wide legal codes centered around the citizen, not the ruler.

In France, before the revolution, different regions followed local customs and the king’s decrees. But after 1789, lawmakers declared that laws came from the people, not the monarch. They enshrined basic rights like equality and free speech, dismantled church courts and special guild privileges, and created the Napoleonic Code—a single set of laws on property, family matters, and merit-based promotion. This code even introduced the revolutionary idea that anyone born in the country automatically became a citizen.

Other European states followed suit. In England, by the late 1600s, Parliament became the supreme lawmaker, replacing royal decrees with parliamentary acts. In Prussia, rulers codified civil rights in the 1700s, all while maintaining a powerful monarchy. These shifts were part of a broader trend of state-building that made law an instrument of national identity and citizen rights.

But nationalism wasn’t the only force shaping legal systems. Colonialism brought European legal frameworks to the rest of the world, often with little regard for indigenous traditions. In India, the British imposed common law through the 1772 Plan of Warren Hastings, sidelining traditional Hindu and Muslim personal laws except in family matters. In Africa, the Berlin Conference of 1884–85 imposed French civil law across West Africa, creating legal systems that still struggle with postcolonial tensions.

In response, colonized societies adapted by merging local customs with European legal codes, creating hybrid systems. For example In Algeria, the Code de l’Indigénat of the 19th century subjected Muslims to harsher penalties than Europeans, sparking anticolonial fatwas that blended Islamic jurisprudence with nationalist rhetoric. A similar blend of colonial and local legal frameworks can be seen in post-independence India, where colonial-era penal codes still exist alongside expanded constitutional rights for marginalized castes and tribes.

⚖️Fun Fact: The Napoleonic Code, created by Napoleon Bonaparte, influenced legal systems around the world, including in countries like Japan, Brazil, and Louisiana in the United States.

5.Factories – Productivity Shapes Policy

Industrial revolutions prompt labor rights, social welfare, and modern civil codes.

The industrial revolution transformed society—not just through technological advances, but by reshaping laws to respond to the harsh realities of factory life. In 19th-century Europe, long working hours and child labor were the norm. Factory workers often endured 14–16-hour days, and children as young as nine were put to work in dangerous conditions.

The UK was one of the first to respond. The 1833 Factory Act limited children aged 9–13 to nine-hour days, banned children under 9 from working, and required two hours of schooling daily. This was the beginning of a wave of similar reforms across Europe. By the late 19th century, nations like France, Belgium, and Germany had enacted similar laws to protect workers, such as Bismarck’s introduction of social insurance programs, which tied health insurance, accident benefits, and pensions to industrial productivity.

As industrialization spread globally, so did the push for labor rights. Mexico set the stage with its 1917 Constitution, enshrining the right to collective bargaining, an eight-hour workday, and the right to strike. Brazil followed suit in the mid-20th century, passing a labor code to protect unions and limit working hours. Meanwhile, South Africa faced a different challenge, as discriminatory laws excluded much of its Black workforce from labor protections. This injustice spurred strikes and eventually led to the 1995 Labour Relations Act, which guaranteed universal collective bargaining rights.

⚖️Fun Fact: The first social insurance program, created in Germany under Bismarck, became the model for many modern welfare systems, including the New Deal in the U.S. during the 1930s.

6.Globalization – The Human Condition Goes Global

Post-war institutions and human rights, economic rules for the world.

In the wake of World War II, the world was faced with the task of rebuilding—not just physically, but legally. The new global order would prioritize human rights, international cooperation, and a restructured economic system.

One of the cornerstones of this new world order was the creation of the United Nations in 1945. Designed to foster international peace and cooperation, the UN provided a platform for countries to discuss and resolve conflicts, setting the stage for the development of global law. Three years later, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights laid out fundamental freedoms that should be guaranteed to all people, regardless of where they were born or their circumstances.

On the economic front, the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, institutions aimed at stabilizing the global economy and encouraging growth in war-torn countries. These financial organizations set strict conditions for their loans—restructuring economies by encouraging privatization and deregulation.

However, this system sometimes led to unintended consequences. In Bolivia, for example, the privatization of natural resources and the imposition of foreign economic policies sparked widespread protests. Because they sold state-owned companies to foreign investors, which led to rising prices for essential services like water and gas, disproportionately affecting the poor. In response, the country took a bold step in 2005 by re-nationalizing its gas industry, a move that reflected growing resistance to the global economic order.

Because they sold state-owned companies to foreign investors, which led to rising prices for essential services like water and gas, disproportionately affecting the poor.

At the same time, the world was grappling with the idea of justice beyond national borders. In 2002, the International Criminal Court (ICC) was established to prosecute individuals responsible for the most heinous crimes, such as genocide and war crimes. But the ICC’s focus on African nations has led to criticism, with many accusing the court of overlooking abuses by Western powers, further complicating the conversation around global justice.

⚖️Fun Fact: Did you know that the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights was translated into over 500 languages, making it one of the most widely translated documents in the world?

7.Climate & Code – The Future is Now

New frontiers: AI, climate justice, and algorithmic accountability.

Welcome to the future—where law meets technology and the planet’s survival. Two major forces are driving legal evolution today: digitalization and climate change. They’re reshaping not only how we live, but how we think about rights, privacy, and responsibility.

Let’s start with the digital age. You’ve probably heard of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which has set a global benchmark for privacy laws. It’s become the gold standard, with countries like Brazil and India quickly following suit. Brazil’s Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD) rolled out in 2020, while India introduced its own Digital Data Protection Act in 2023.

Together, these laws cover over 1.5 billion people, regulating how companies handle personal data, and hitting violators with fines as high as 4% of global turnover. It’s a huge step toward controlling how your data is collected, stored, and sold—basically giving people more say over their digital selves.

But not everyone’s on board with this. Countries like China and Russia are going in the opposite direction. China’s Great Firewall blocks access to over 10,000 foreign websites and censors social platforms, while Russia’s Sovereign Internet Law lets the government isolate its network and control what citizens see online. The tension between freedom and control is becoming a major legal battleground.

Now, let’s talk about climate change—a force just as disruptive, but in a completely different way. Rising sea levels, extreme weather patterns, and natural disasters are forcing countries to rethink their responsibility to the planet and its people. In 2023, the island nation of Vanuatu led a coalition of Pacific Island nations, urging the International Court of Justice to define state responsibilities for climate harm.

As rising seas threaten low-lying communities, these nations are demanding legal recognition that climate change isn’t just an environmental issue—it’s a human rights issue.

On the horizon, we’re also seeing laws that aim to hold corporations and governments accountable for their carbon footprints. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, set to launch in 2026, will slap import fees on goods from high-emission countries. It’s a move that could affect up to €500 billion in trade—forcing nations and industries to pay a price for pollution.

Finally, we get to the rise of AI—a technology that’s changing the way we make decisions, often in ways we don’t fully understand. Just like privacy laws are evolving, laws around AI are catching up. In 2024, the EU’s AI Act will ban facial recognition in public spaces, trying to keep this technology in check before it becomes too invasive.

In Kenya, the Data Protection Act of 2021 prohibits AI-driven voter profiling, while India’s Digital India Act mandates transparency on how algorithms work, addressing potential biases, especially around caste and gender.

AI is also making waves in how we think about accountability. As more and more decisions are made by machines, we’re left to ask: Who’s responsible when AI gets it wrong? Laws are starting to answer that question, but we’re still in the early stages.

These new frontiers—AI, climate justice, and data privacy—are challenging our current legal frameworks. What happens when laws from different countries, cultures, and ideologies collide? How do we create a global system that balances innovation with human rights? The next chapter of law is still being written, and we’re all part of it.

⚖️Fun Fact: The GDPR’s reach extends far beyond Europe. Any company that handles the data of EU citizens must comply with its strict rules, even if they’re based outside Europe. This has made GDPR one of the most influential laws in the world, shaping data protection standards everywhere.

Conclusion – The Law That Grows With Us

From the primal instincts of tribes to the cold logic of algorithms, if you look carefully you will notice that since the dawn of humanity law is used for two things- survival and growth. It ensures that however new the situation is humanity finds a way to navigate it without tearing itself apart, while also fostering its usefulness and paving the way for the next step in human evolution.

Each era brought its own challenges—and its own legal responses. Kingdoms gave us divine authority; nations gave us democracy and codified rights. Industrialization forced us to reckon with labor and welfare, while globalization exposed both the power and the hypocrisy of international law. And now, as we stare down the twin storms of climate collapse and AI disruption, we find ourselves once again rewriting the rules.

But here’s the kicker: law doesn’t just follow society—it shapes it. The Napoleonic Code didn’t just reflect post-revolutionary France; it molded modern civil law. The GDPR didn’t just protect privacy; it redefined how companies operate worldwide. The courts, the codes, the constitutions—they’re not just tools. They’re mirrors. They show us who we were, who we are, and who we’re trying to become.

So, what’s next?

That depends on what we demand from the law—and what we demand from each other. Because if history has shown us anything, it’s that law isn’t written in stone. It’s written in time.

Appreciating